I came into preparations for The Papercut Haggadah with a passing familiarity with Passover and the elements of the Seder, but no idea of the richness of the tradition of the Haggadah or its development both as a body of texts and rituals, and as a written or printed artifact.

One of the benefits of being a university museum is having access to varied and valuable resources on campus. Here at Saint Louis University, one of our great treasures is the SLU Libraries Department of Special Collections, and in particular the Vatican Film Library, a research collection for the study of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts and the texts they contain. It is formed around a core collection of more than 37,000 microfilmed manuscripts from the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, ranging in date from the fourth century AD through the seventeenth century and covering a broad spectrum of subjects. In addition to the microfilm, the collection includes many actual manuscripts as well as reproductions and reference materials.

We turned to the friendly and helpful staff of the Special Collections division to see if they had any historical examples of Haggadot that we could look at for reference. The response was exceptional. Not only were we able to see samples of pages from illuminated and printed Haggadot, we were able to make arrangements to borrow a number of volumes to include in the exhibition, so that all of our visitors could see these historical antecedents as well. We selected items that relate to aspects of Archie Granot’s project, such as the textual passages illuminated, or similar design elements.

For instance, we had noticed in Granot’s papercuts that certain Hebrew letters were frequently elongated or otherwise distorted. It soon became evident that this was not an arbitrary artistic choice, but a practice rooted in centuries of handwritten Torah scrolls, allowing scribes to create perfectly justified columns of text.

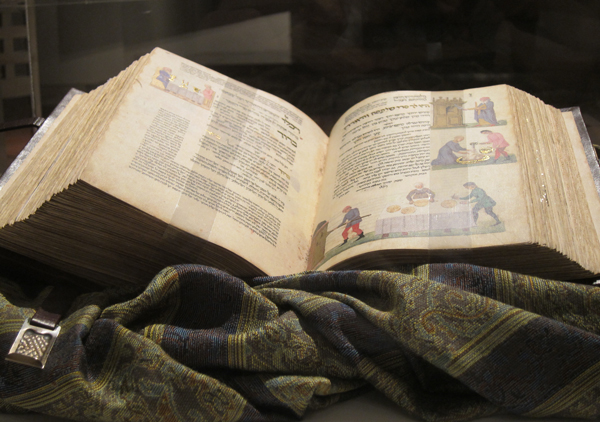

The most notable object we have on loan is a magnificent facsimile of a 15th-century illuminated manuscript called the Rothschild Miscellany.

The original volume was commissioned by Moses ben Yekuthiel Hakohen during a period when Italian Jews experienced exceptional scholarly and artistic activity as well as social mobility. The most elegantly and lavishly executed Hebrew manuscript of that era, it is comprised of more than 37 religious and secular works. Among the religious books are Psalms, Proverbs, and Job, and a yearly prayer book including the Passover Haggadah, while the secular books include philosophical, moralistic, and scientific treatises. The text throughout the manuscript is accompanied by marginal notes and commentaries. Of 948 pages, 816 are decorated in vibrant colors, gold and silver.

This painstakingly produced facsimile is open to the beginning section of the Haggadah. It is common in historical Haggadot to find depictions of the actions or rituals prescribed in the text. The illustrations on the righthand page depict preparations preceding Passover, including brushing up crumbs of leaven with a feather, burning the leftover leaven, and baking matzah. Granot references this practice in one of the pages of The Papercut Haggadah.

We are grateful to the staff of Saint Louis University Libraries Special Collections for their kind assistance and enriching the experience of our visitors.

— David Brinker, Assistant Director